“the EU DOESN’T understand the eastern European oligarch way of thinking”

Lajos Tihanyi, Family, 1921 © Copyright of the work expired, Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest - Hungarian National Gallery, 2023

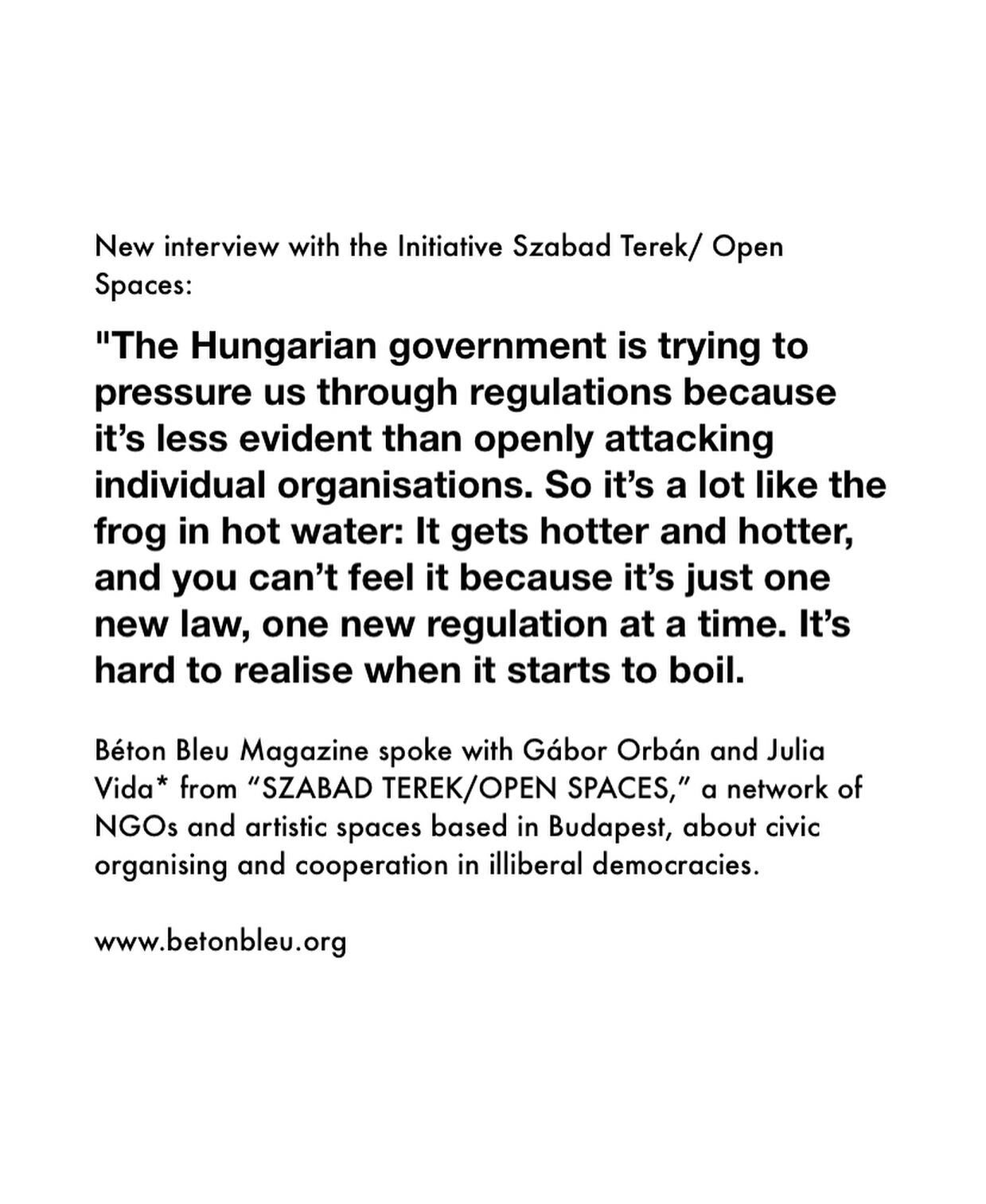

BÉTON BLEU MAGAZINE x Szabad Terek

Under the reign of the Hungarian ultra-conservative party Fidesz, Hungary has increased pressure on civil organizations and art institutions. Béton Bleu Magazine spoke with Gábor Orbán and Julia Vida* from “SZABAD TEREK/OPEN SPACES,” a network of NGOs and artistic spaces based in Budapest, about civic organising and cooperation in illiberal democracies.

Béton Bleu Magazine: “Szabad Terek” (Open Spaces) started in 2017 as a network that brings together independent community spaces and civil society organizations in Budapest. Was this a response to pressure from the governing party, Fidesz?

Szabad Terek: More or less. Before we started, there were attacks against civic organizations and community places. Not by the government but by municipalities. They wanted to close community places like Aurora in Budapest, a community place and incubator house that provides a space for the LGBTQ community, independent newspapers, and civic organizations. In another case, the mayor of the city Pécs, Zsolt Páva, went so far as to get in touch with the real estate owner to prevent a civic organization called the Power of Humanity from having its headquarters in the city and thus prevented them from operating. You could see similar things happening in other cities.

BB: What was the goal of starting “Szabad Terek/Open Spaces”?

ST: We thought that it would be essential to build a network of organizations that share the same values because we believed we could be stronger together. Today, we have 60 members in nine cities. We aim to cooperate, learn from each other, and be a strong network.

„The government is trying to pressure us through regulations because it’s less evident than openly attacking individual organisations. So it’s a lot like the frog in hot water: It gets hotter and hotter, and you can’t feel it because it’s just one new law, one new regulation at a time. It’s hard to realize when it starts to boil.“

Mihály Biró, Red Parliament!, 1919 © Copyright of the work expired, Photo: Museum of Fine Arts - Hungarian National Gallery, 2023

BB: Do you still feel the governmental pressure hindering your work?

ST: Yes. It started with one or two places, but now all the organizations and the places are under the same pressure from the government, which implements new rules and laws to make it harder and harder to operate. We have fewer and fewer funds and fewer and fewer places to go to. They are trying to pressure us through regulations because it’s less evident than openly attacking individual organizations. So it's a lot like the frog in hot water. It gets hotter and hotter, and you can't feel it because it’s just one new law, one new regulation at a time. It's hard to realize when it starts to boil.

BB: What kind of regulations is the Hungarian government enforcing to prevent liberal organisations to work?

ST: For example, some regulations say that certain places, such as clubs and community centers, have to close at midnight. This is difficult because for many businesses, most of the income is made after midnight. Secondly, there are fewer national funds for non-profit organizations, art groups, or theatrical events. It’s tough to maintain a place because you can’t pay the people you work with. The tax system puts additional pressure on us. It constantly changes, and it's getting harder to find people who are willing to work for a civic organization for less and less money. Working for civic organizations is a luxury thing in Hungary.

Another way of hitting NGOs is to only fund government-friendly NGOs. And obviously, there is no such thing as a government-friendly NGO. Those who claim to be are just little pets of Orbàn. Organizations like ours survive on EU funding. It used to be very easy to work with contractors because of a specific tax system, but this summer, they cut the funding through this program in half, from one minute to the next. At the same time, prices for utilities increased, which also hit NGOs. These are the hidden steps that are not explicit, that you cannot necessarily see. They say, ‘we are not targeting NGOs,’ but the result is the same.

BB: Has the governmental attack on independent NGOs changed the cultural landscape in Hungary?

ST: The number of cultural events and theaters might be the same, but those theaters and events and festivals are much closer to the government. Those who are not can barely survive. They never say that you can't do it. The government never says that these kinds of events can't be happening. You just don't get enough money to do it.

Hugó Scheiber, Self-portrait, 1928/30 © Copyright of the work expired, Photo: Janus Pannonius Museum, Pécs

„The number of cultural events and theaters might be the same, but those theaters and events and festivals are much closer to the government. Those who are not, can barely survive.“

BB: How free are cultural institutions and artists to express themselves, organize events, or have exhibitions? Can you give a concrete example?

ST: There are many examples of self-censorship, especially at the local level. Independent theaters or companies are afraid they might get some kind of punishment from the local government, especially in cities where the local government is Fidesz. I think it’s really hard to have a space for independent or alternative cultural events.

The way the artistic scene develops has wholly changed. It used to be the case that new ideas and ways of expression start in the small alternative, independent groups and then reach the mainstream, the big theaters. Today, many artists and directors from the government-supported mainstream theater infiltrate the alternative scene. This way, new ideas disappear because the audience is not interested in them anymore. The alternative scene will disappear.

„The Hungarian government never says that these kinds of independent events cannot happen. You just don’t get enough money to do it. “

Károly Kernstok, Younglings, 1909 © Copyright of the work expired

BB: Do you feel there is less diversity in today’s Hungary?

ST: Yes, many art groups and civic organizations experience it. People are scared to participate because they fear the consequences, even in their day jobs. Most people, especially in smaller cities, have some kind of connection to the municipalities or government companies. Many people think they have to behave a certain way and stay away from certain places like independent theaters. As a consequence, there are fewer theatrical events. There are fewer scripts. A lot of directors and artists have left the country. It happens day by day, and we can feel it.

BB: Are there any efforts in the community to prevent the artistic brain drain in Hungary?

ST: With rising energy prices, more and more people just try to survive day by day. The question for them is how do we survive the winter. How can we pay our bills? That makes it hard to think about things like how to build a democracy and how to help civic organizations that are in trouble. There is also a huge divide in Hungary that makes it hard to build a united resistance truly. When three people come together, they separate five minutes later because they will find the one thing they do not understand or agree on. We lost our capability to be a community and to build a group and fight for something.

László Moholy-Nagy, Construction, c. 1922 © Copyright to the work expired, Photo: bpk / Kupferstichkabinett, SMB / Jörg P. Anders

BB: Do you think the EU has done enough to help organizations like yours and artists in general?

SS: You can see that the EU is trying to intervene, but it’s very hard to point at one thing to prove wrongdoing by the government, decisions that went too far. It’s like a fish or a snake; when you try to grab it, it slips out of your hands. I do think there are a lot of funds being held back because of legislation and corruption. But that also means there's less money in the country, which hurts us too.

BB: How could EU funding reach you better?

ST: Organisations like ours are starving, and many more organizations will close if things don’t change. Part of the funds being withheld should go directly to civic organizations because we do the government's work. We are the ones who care about children, who care about European laws and values. We care about refugees, minorities, and LGBTQ rights – all the things the government doesn’t care about.

BB: Do you have an example?

ST: In the case of schools, as a parent, you have to pay for books, soap, towels, and food. You have to pay for a lot of things you have to pay as a parent. And now the schools collect money for heating. There are civic organizations that try to help these families. What does the government do? Instead of paying for this, they build highways and sports stadiums.

„With rising energy prices, more and more people just try to survive day by day. The question for them is how do we survive the winter. How can we pay our bills? That makes it hard to think about things like how to build a democracy and how to help civic organizations that are in trouble.“

BB: Why is it so hard for the EU to intervene?

ST: Maybe they don’t understand the eastern European oligarch way of thinking. The EU Commission always thinks it can pressure the Hungarian government into changing its course of action. However, they will only pretend to do that at a surface level. Real change will not occur. To be honest, I don't think it's possible to cooperate with the Fidesz government because they only see their own advantage – and by their own advantage, I don't mean that of the country.

BB: Are you hopeful that the cultural scene in Hungary will survive?

ST: I don’t know whether the people who left the country will ever come back. And I think the people that stayed behind are very familiar with the current system. You just go along and know how to navigate it. You’re swimming in water that’s not too warm or cold, so to speak. It's not ideal, but maybe it's better than being outside. So I think the question is whether we can change our attitude. On a national level, it should take decades to change attitudes toward a system that is so familiar to a lot of people. The question is whether the young people will stay in Hungary or not. Because if they leave the country, there will only be the old ones who only know this system.

It's hard to keep up the faith, especially when you see institutions being destroyed. At one point, they replaced the teachers and the leadership of the University of Theatre and Film (SZFE) in Budapest with Fidesz’s people. The students organized an Occupy movement for a couple of months to protest this decision. But then they had to leave because of Covid, at least that's what the government said. I don’t know how they will rebuild such an institution with such a long tradition and a very important role in Hungarian culture.

„I think it’s impossible to change the current situation when all the good and famous directors and teachers left the country.“

BB: So some damage that has been done to the cultural scene will be very hard to repair.

ST: I think it's impossible to change the current situation when all the good and famous directors and teachers left the country. There will be a new generation taught by teachers and artists, and journalists who are not teachers, artists, or journalists but who work for the governmental national radio and television and participate in the fake news industry, for example. They will be the next generation of Hungarian journalists and artists. It is very hard to change this system democratically; you will have to start from scratch.

The older Hungarians never learned how to live in a democracy. Before Fidesz took over in 2010 and after the regime change in 89’, there was not enough time for them to learn it. And now there's a risk that the young people will also not learn it because they are brought up in an autocracy. For real change to happen, people must learn how to live in a democracy.

Hugó Scheiber, On the tramway, 1926, Courtesy Ernst Galerie, Budapest, © copyright on the work expired

BB: How can that happen?

SS: Many people think the change should come from the EU because we can't do it ourselves. But I disagree. Change never comes from outside. Waiting for the EU to make declarations and decisions won't help us. I think we have to change the way people think about Hungary. And that's why I think it's more important to strengthen organizations in Hungary that connect to the people on the ground, in the cities. That is much more important than signing petitions or demanding declarations.

Thank you so much for your time.

* Gábor and Julia have since left Szabad Terek. Their answers reflect the view of the organisation.

About:

Open Spaces (Szabad Terek) is a Hungarian network that brings together independent community spaces with civil society organizations. In its own words, the network was established in 2017 to broaden the shrinking spaces of civil society in Hungary and to work for a more open and more democratic society. The aim is to increase cohesion and generate fruitful cooperation between the members and inspire and support them to create projects together that promote their common values.

Website: https://szabadterek.hu/english/

Interview: Thorsten Schröder

27/01/2023

FIND more curated content on instagram: @bétonbleumagazine